Greg Husak

When planning a practice, it is important to think about the personnel and

goals of a practice. For instance, a fall practice for a college team is going

to have very different objectives than a fall practice for an elite open team.

The college team might be trying to have a lot of fun to “set the hook” with

new players and give a lot of reps to players still learning the game, while

an elite team is tuning up for the peak of their season and should be focusing

on consistent execution of skills. Recognizing the goals of a practice is

critical in its design. This brief article will focus more on elite practices.

Early in my ultimate career I was exposed to high level college and pro

football practices. One of the things that I was most surprised by was that

the players were only on the field for two hours. I was used to ultimate

practices which went no less than three hours, and I figured top athletes were

doing the same thing. However, in those two hours of a football practice there

was more attention to detail, the movements were more scripted and the overall

focus was very different than my experience with ultimate practices. In short,

football players seemed to be getting more out of a two hour practice than we

got out of three.

This got me thinking more about designing practices for top-level teams.

Rather than doing a drill for a mind-numbing number of repetitions at a

continuous energy level that prevented execution at 100% speed, what if we did

two drills, but only did 6 reps of each drill, and did each rep at 100% speed

with some rest in between? The effects seemed to be very positive. The team

was much more focused, and it seemed that there were no wasted reps. Further,

the movements and timing of drills simulated actual play more closely than the

old version.

Some of the things that were required in order to get this focus and buy-in to

this “new” style was a more thorough planning of the practice, development of

new, stimulating drills, and finally talking to the team at the start and

letting them know which drills would be done, when we would rest, and a

general flow of the practice. When players saw that there was a clear plan,

with a focus on particular skills, they were responsive to this change and the

overall level of intensity at practice improved.

Finally, we got away from a mindset that a practice that lasted less than

three hours didn’t fully accomplish something. If the team could meet the

objectives in two-and-a-half hours, then we didn’t need to practice longer.

Incidentally, playing with full focus and full effort typically left players

feeling equally exhausted after a practice that wasn’t as long as before.

Overall, we were able to accomplish as much or more, in a shorter time, and at

a level of play and focus that stimulated what was required on the field

during competition.

Pat McCarthy

Nearly every team I’ve played on had what I would call the “traditional”

ultimate warm up. You jog/plyo/stretch in some combination, and then you do

some set of drills which can be roughly summarized as: the down field under

“cutting” drill (Go To, etc), the dump/swing/continue “handler” drill and the

huck drill. There are lots of different flavors of them, with or without

marks, where you start, etc, but at their core, these drills focus on 2 or 3

players while everyone else is watching. While these drills are easy to set up

and run, they are incredibly inefficient from a “maximize your time”

perspective. Even worse, you’re constantly battling team wide focus issues in

these drills with artificial goals because you really only need to be focused

20% of the time to do the drills perfectly (20 completions in a row then we’re

done!). Before you know it, 20-30 minutes have passed and you’re not much

closer to being ready to play. I don’t feel qualified to say what the best

jog/plyo/stretch phase looks like, but I can confidently say that the drill

aspect of warm up can be much improved if you focus on three main goals.

1. Get your team Focused

At the end of the warm up your team should be alert and attentive. The entire

warm up should take 100% focus from every player to execute. If this is all

you get out of your warm up, at least you have a team that’s ready for the

rest of practice. Warm up drills should involve 2-3 players at most.

2. Realistic reps at the basic mechanics of ultimate

Cut. Change directions. Catch. Set your feet after the catch. Go from catch to

a throwing grip. Pivot and transition from one grip to the other. Make clean

break mark moves and throws. Cut again. Get lots of touches for each player

(in the range of 100) so that everyone is comfortable making the basic

ultimate plays that the rest of your practice plan depends on.

3. Get it done quickly

The Drill phase of warm up should be completed in 10 minutes or less. By

shaving 10 minutes off your warm up, you save 10 hours of practice time over

the course of the college season.

My favorite warm up is a drill we call “Dishie Warm Ups”. They take 5 minutes

to run, and each player gets roughly 100 catches & throws, 60 pivots & grip

changes & 30 cuts. Each of these should build focus; if your team does one set

lazily, or has lots of turnovers, don’t be afraid to stop the drill and

restart it. You can easily add a mark to around dishies, or change the

distance between the throwing partners to get more variation in your warm up.

Partner up with a disc, set up 10 yards apart and go 70-90 yards up and back

doing:

- Regular Dishies: Complete running passes to each other up and down the field. Try to throw less than 2 steps after the catch (ideally within 1 step).

- Inside Out Dishies: Repeat with a pump fake to the outside, then hitting your partner with an in stride inside out throw. Focus on a quick pivot & throw.

- Around Dishies: Partner goes up the line, then cuts for an around throw off of the pump fake. The timing is different on this one than it is for inside out dishies. Take the imaginary downfield look, then inside, then beat your imaginary mark with a quick move to the around throw.

Peri Kurshan

Practice planning can be daunting and it’s often hard to know where to start.

It can be difficult to strike the right balance between fun and intense,

learning and playing, covering everything and getting enough reps on any

individual thing, etc. In my experience, it helps to have a broad, season-long

outline from which to flesh out individual practices. This means having a

rough idea of all the different strategies you want to cover in a season

(specific offenses, specific defenses, fundamentals, etc), and making sure

there are enough practices to cover everything (and if there aren’t, then to

scale back your expectations of how much to cover in the season!). Keep in

mind that you need to save a few practices at the end of the season for

consolidation rather than learning new things. I’ve found that it’s better to

cover fewer things and have everyone really on the same page than to try to

cram too many offenses or defenses in. I usually try to cover no more than 1-2

concepts per practice (for a 4 hour practice- for a shorter practice scale it

back to no more than 1). It’s also useful to have enough extra practices

allocated for things that come up during the season, for example something you

realize you need to work on after a tournament.

Once you have your broad outline set, and you’ve decided what you’re going to

be covering in a particular practice, then it’s time to plan out the details

of how the practice will be run. On Brute Squad we start every practice with a

nice long warm up routine (it gets cold in Boston, and we don’t want any

preventable injuries at practice!), followed by a warm-up drill that involves

throwing with lots of touches, and enough moving around to build on the warm-

up. We then go right into a quick game to 3. The goal of this game is to

immediately get people’s intensity up and get them into the practice

mentality. Jumping right into a game gets people’s minds off of whatever else

is going on in their lives and helps them focus on Ultimate. It’s also good

practice for coming out strong, since there’s no time to come back from an

early deficit!

After the game to 3, it’s time to start introducing whatever concept we’re

working on that day, whether it’s a 3 person cup zone defense, or a horizontal

stack man offense, or maybe even just a focus on cutting fundamentals. Having

a large white board to use to explain concepts is often helpful, but after you

diagram it out, you may want to walk through it on the field as well. In any

case, keep the talking portion of the practice to a minimum- this is most

often where you’ll lose people’s focus if you tend to go on and on about

things. Keeping things simple is often better than giving an exhaustive

treatise on every aspect of what you’re discussing!

Depending on what you’re working on, it’s usually helpful to try to break

things down into minimal components, and then drill the individual components.

For example, if we’re working on man defense, we might start out by doing a

drill that just works on proper footwork and staying on the open side of your

player. Then after a while we might incorporate adjustments you make once the

disc is in the air. Basically, the more you can break things down, the easier

it will be for people to incorporate what you’re trying to teach. And if each

drill builds on the previous one, slowly putting the pieces together, your

players will get to solidify their muscle memory for one action while adding

another one. With all this drilling, you can see how one concept can end up

taking up a large portion of a practice!

Finally, you can only spend so much time drilling- it’s important to take

things back to realistic, game situations. We usually end practice with

focused scrimmages, in which we try to incorporate what we’ve learned that day

either by forcing the defense to throw a particular D, or by adding incentives

to the scrimmage (for example, if we were working on deep defense, we might

use a 2-point line to encourage deep throws). Ending on a scrimmage also

ensures that people get a chance to do what they’re really there to do- play

and have fun!

Ben Wiggins

Minutes at practice are precious. Here are my 5 relatively simple ways to

maximize the amount of growth you can foster from each of your practices. At

the end, I’ve included an example set of 3 practices to try and illustrate

these points.

1) Use your warm-up time effectively

Warm-ups take a large percentage of total practice time. To focus that effort,

I like to include warm-up drills or games that give a good mental introduction

to the purpose of later practice drills. I’ll try to use plyometrics or other

movements that foreshadow the movements we’ll be trying to teach later. I like

to start with a warm-up game for many practices as well, and these games can

usually be tailored to work with the later specifics.

We all learn from our mistakes, and we are very good at learning from

experience. Warm-up time doesn’t have to be focused or consciously driven for

the players. As a coach, this is where I am putting drills that can give

benefit without being discussed overtly or even introduced at all. You can’t

expect players to come straight from class or work or their families and act

professionally in the first minute. Even pros need time to get in the right

frame. But we can tailor those introductions to help the warm-up put them in a

receptive and ready state.

2) Cover topics in multiple practices

When you think about the school classes you have taken: did you spend 5 hours

in a row learning math every week, or did you go to class for 1 hour each day?

Spreading learning out gives players a much better chance to internalize new

strategies or fundamentals. We can do this by running similar drills or

situations in multiple practice plans.

For example, let’s say we have 3 drills that we want to run for ~30 minutes of

total time each. Those drills are similar, with “A” being a simplified

fundamental drill and “C” being the very advanced application drill. We could

run those drills all on Monday and spend a complete 90 minutes on that topic.

This would be easy to plan. Players would spend a long time on similar drills,

so we might lose some effective time due to boredom. Also, players would only

have one night after the practice to be mulling those topics over when drills

or done. Which means just one post-practice meal to discuss and no practices

that players can come in already thinking about the topic.

Alternatively, we can maximize those benefits by running these drills in

series throughout the week. This gives players lots of time to think and

prepare. You’ll catch your team by surprise less, which is a good thing with

complicated topics. I’ve tried to show an example of this in the practice

plans below.

3) Focus on fewer topics

In other words, don’t try to cover everything. Given limited practice time,

work on those topics that are most important. If something is not going to

give a real return to your team, then don’t practice it. Ideally, the perfect

team has probably practiced everything at least once, but that just isn’t

realistic for a college or high-school team. If you can only practice twice

per week, then trying to run two different offenses is not going to help. Do

one well. If you are not going to use a 1-3-3 zone, don’t learn it. Do you

really need to spend time teaching all of your players how to call plays on

turnover situations? No! Use those reps to teach your handlers how to make

these calls, and use the extra rep time to learn it well.

Maybe most prevalent, in my opinion, is trying to teach solid continuation

(aka ‘flow’) cutting. This is very difficult and time-consuming to teach. It

requires teaching vision and anticipation, which are long-term learning goals.

I feel like many youth teams spend massive amounts of time learning how to

play flow offense against solid man-to-man schemes…and then spend their

entire season playing against poaching person-D or zone. Those teams would

have been better served spending more practice time on zone and learning it

well.

As coaches, we don’t know what our teams will see…but we do need to give

them enough tools to have success. But when you know what to expect then you

should tailor your game to beat it. If you are worried about depriving your

players of the balanced Ultimate education for future teams, know this:

players that learn a few skills extremely well have a much easier time

learning other skills at a high level. Players that learn many skills poorly

will struggle when they have to learn any particular skill at a higher level.

You may be serving your young players better by helping them master a single

skill rather than having a mediocre grasp on ten skills.

(In the example below, I am writing for a team that has decided that

downfield defense is their top priority, and they believe that this is going

to help them even if they spend less time on other defensive priorities like

zone, poaching, etc.)

4) Eliminate pulls

The time between pulls can be a huge waste of practice time. When you add up

everything that goes into walking to the line, discussing the play, signaling,

pulling, walking to the brick…it adds up fast. You can be much more

efficient by running more game situation from a stopped-disc. Or by breaking

your team into 3 squads, and having two teams pulling to a single O-team so

that the D can discuss and be ready to pull very quickly.

Playing uptempo at practice will ready your team for observed games with time

limits, and it saves a ton of time. With that extra time, you can talk as a

team about details or run extra reps. You have to play real Ultimate

sometime…save that for scrimmages that aren’t focused on a single topic or

that are long enough to simulate a game.

5) Be prepared

If you’ve read this far, then you really care about creating efficient

practices. So I’m probably preaching to the choir here. Every minute that you

aren’t prepared at practice is 20-25 minutes from your teams’ individual

minutes that could have gone into becoming a better player or a better team.

Write your notes ahead of time. Have a plan. If nothing else, your players

will feel more respected and more valued, and they will work harder because of

it.

Most importantly; once you have a good plan, you can deviate from that plan

intelligently. If you’ve planned for 20 minutes of a particular drill, then

you can change at minute 19 for extra time if you think you are on the verge

of a team breakthrough. Alternatively, you can back off the pace and re-

simplify drills if the concepts aren’t knitting together like you’d hoped. Or

switch topics more rapidly if they are coming easily to your team. Those kinds

of deviations are where coaches and team leaders help make huge advances…and

you can’t do them when you are trying to figure out the plan during the

practice.

With those things said, here is my example for a set of three 2.5-hour

practices, with the focus being improving individual downfield defense:

Tuesday

- 0:00 Warm-up jogging, normal plyos

- 0:15 Partner plyos: for the last 5-6 movements, one partner does the plyo for 5-15 yards, then turns and jogs 75% back to the line. Partner traces them back, trying to anticipate the turn.

- 0:20 Water

- 0:23 General Offensive Drill 1 (something to get touches and work on non-D stuff)

- 0:33 Huddle talk: Downfield defense

- We can’t stop everything against good players, but we can make cutters less effective by taking away their best option and forcing them to do something else

- We’ll anticipate cuts by reading the field and reading our player’s body language. In these practices, we’ll be working mostly on reading body language to be ready for the race to the disc when it starts

- Work on the footwork now, even if it makes you slower in the short-run. Eventually, this will pay off and we will be able to put more pressure on more cuts against better players.

- 0:38 Defensive Drill A: Intro 1v1 cutting D

- 1 player from a downfield spot guarding 1 cutter. No disc. Work on lining up correctly, and on anticipating and moving well in the first 4 steps. Drill is over after 4-5 steps.

- 0:48 Defensive Drill B: Beginning 1v1 cutting D

- Same drill, now cutting fully. Still no disc for first few reps each, then with throw on the sideline and a sideline force. Stop drill whenever fundamentals from Drill A are not being met. Working up to staying with players and maintaining position, not giving up hips until cutter has determined either in or deep cut. Encourage good footwork, not just whether they get the block or not.

- 1:00 water break

- 1:05 Defensive Drill C: 1v1 from Continuation

- Similar drill, now 2v2. If the first cutter can’t get the disc, they can clear and let the second cutter attack. Focusing on maintaining position, lining up correctly on a cutter in motion to prevent either in or deep cuts, depending on matchup/location.

- 1:18 Scrimmage w/ Focus #1

- 2 teams, each point starting from the corner cone (no pulling). Each team gets 5 possessions in a row.

- Defense working on winning the first 4 steps of individual matchups. On turnovers, no fast break (giving extra chances to work on lining up, anticipating and stopping cutters)

- 1:50 water break

- 1:52 Discussion with team: What things from drills worked, and what didn’t?

- 1:57 Defensive Drill D: 1v1 Breakside cutting

- Similar drill form to A, B, C, but from the middle of the field

- Focus on tracing parallel to cutter, so as to eliminate crossing cuts back to the live side and not overcommiting on in-moves

- 2:10 Scrimmage w/ Focus #2 (Skip this if you are running long, or extend this if you have extra time)

- Same format as #1

- Goals are 1 point each, but now so are any full cuts that are stopped and the thrower is forced to dump (play continues)

- 2:20 Cooldown, stretch, recap of major points in initial discussion

Thursday

- 0:00 Warm-up plyos

- Instead of jogging to get loose, players are in pairs with a cone on the ground. At 50-60%, one player is Offense and should jog away from the cone and back about 8 times. The defender should try to stay with the jogging player, anticipating the turns back to the cone. Switch, twice each.

- 0:20 Water

- 0:23 General Offensive Drill 2 (something to get touches and work on non-D stuff)

- 0:33 Huddle talk: Downfield defense

- Repeat major points from yesterday.

- New point: Understanding which race the offense wants to run is a fundamental. Club defenders get better with age, not worse, because they understand offensive players more and more thoroughly.

- 0:37 Defensive Drill A in small groups

- 0:42 Defensive Drill B in one group, don’t add a disc until the fundamentals start to look good.

- 0:52 water break

- 0:55 Defensive Drill E

- Begin with a vertically stacked pair from the middle of the field. Disc in the middle.

- For the first few each, Offense must cut on the live side of the field

- After that, Offense has the choice of cutting to the break side (basically melding Drills C and D together here.

- 1:10 water break (this is a high-intensity drill, so we are breaking more often)

- 1:15 Defensive Drill F Options

- Anti-Horizontal Option: Start the offensive pair side by side

- Anti-Vertical Option: Add a third vertically stacked cutter.

- My suggestion: Do not start by talking about ‘what should happen’. This removes their opportunity to figure it on their own, and hamstrings the offensive cutters into a rigid form. Give players a full opportunity to work this out on their own, to be beat repeatedly and then make adjustments. Even young players will figure this out, or at least be forced to grapple with it. Give everyone 2-3 reps on D before you talk about what we want. Then, make adjustments and continue with at least 3-4 more reps each.

- 1:45 Water break

- 1:50 Run D drill F again.

- This is where the coaches earns the big bucks; either increase the difficulty with more passes, or more offensive players, or a handler than can receive a dump. Or, if this is all coming fast, back off a little by doing the other sideline (the one you didn’t do yesterday) or doing horizontal on the sideline to give a new look but not increase the abstract difficulty. Do what is right for your team’s next step, not necessarily what you need to get to point B before Saturday.

- 2:05 Conditioning: 1v1 Deep Drill

- 2:15 Stretch, recap major points, done

Saturday

- 0:00 Warm-ups: Do same partner-cone-jog warmups, then plyos. Finish with defensive plyos like on Tuesday.

- 0:20 Water break

- 0:25 Drills B and C in small groups, 3-4 reps each

- 0:35 Huddle talk

- Today’s focus: Applying what we are working on to game situations. These skills are most useful in small bursts throughout a point, but when they are necessary they are crucial. Throughout today’s games, our goals are:

- Excellent- use these skills to stop flow cuts effectively and prevent throws (or block them)

- Great- sometimes use these skills instead of just trying to run faster than our opponents. Get a few stops/blocks using these skills.

- Good- Notice the opportunities (ourselves, not the coach) for where we could have used these skills. Identify those times and positions, and be ready to get better at using them.

- 0:42 Drill F (in whatever variation your team plays offense most regularly)

- 0:52 Game 1

- If you have 21 players, split into three teams. Each team gets 5 possessions in a row on O, against alternating D.

- If you have less than 21, divide into two teams (randomly). Each teams gets 5 possessions in a row, 1 possession each max (after two turns, reset and play the next point).

- No pulls. Start each possession from the brick. No fast breaks, to work on lining up off of a turn. Special rule: One extra point if the first throw for the offense goes backwards to the dump. Dump defenders are not allowed to poach on the first throw. Continue the play as normal, but add that as a point in the score.

- 1:22 Water break

- 1:27 Game 2

- Same format as the first game. Special rule: After the game, every player has 3 conditioning sprints. If you successfully stop/defend/block a downfield cut, you get a -1 sprint. [Ideally, a coach or assistant coach is marking this from the sideline and calling out player names when they get one to give immediate positive feedback.].

- 2:10 Water break

- 2:15 Conditioning: Skyball

- 2:22 Stretch, recap major points of what we’ve accomplished this week, done

Shane Rubenfeld

Everything that happens at practice should be a building block and not an

isolated event. You need to design practices behind a theme that’s overtly

stated to the whole team and repeated often throughout the day. Never let the

participants lose track of the day’s goal or remain unclear about the lesson

at hand. Emphasizing concrete points of focus over the course of practice as

well as the course of the season gives your players a measure of their

progress, in addition to game-time tools. Here are five points to consider

when drawing up and running practice:

1) When you introduce a concept, tie it to your overarching offensive or

defensive theme. Be clear about the exact actions to be performed, and under

what conditions. Try to maintain consistency and keep clear delineation

between ‘system’ – your team’s rules– and exceptions to them.

2) Avoid switching gears with no transitions. Don’t switch suddenly from

one practice point to another; if your two lessons don’t relate somehow, you

can probably save one for the next practice.

3) Punish for lapses in the lesson of the day, not for every fault. A lot

of teams run sprints or have other repercussions for turnovers, poor choices

or other screw-ups. If your team employs such a system, be judicious about

assigning them when you’re stressing the lesson of the day. Sprints for drops

when you’re focusing on the cutting system or on breaking the mark will

distract and waste minutes. Instead, how about sprints for the wrong cutting

and clearing, or for getting broken?

4) Scrimmage with intent. Don’t just release the hounds after the teaching

drill to go play ultimate. Mix up scrimmage rules in ways that keep the team

focused on the lesson of the day: 7v0, half-field possessions, turnover limits

with repulls, always starting the disc trapped on a sideline are all tweaks

you can work in that will keep players trying to make each other better, and

not just win an insignificant scrimmage. SIDE NOTE: Sprints are boring. Can

you think of ways to ‘condition with intent’ in the same way?

5) Review at end of practice. Challenge the players to mentally go over

the lessons of the day. Again, when reviewing, place the lessons of the day

into the larger strategic concept your team is trying to adopt.

Ryan Thompson

Great practices don’t just happen. A lot of work goes on behind the scenes to

plan practices that run smoothly and effortlessly, as well as accomplishing

the main goal of making the team better.

Plan your practices in advance - not just the drills for one practice, but

figure out what concepts you want and need to cover over the course of the

season. Then break down the concepts and spread them over the available

practices. It’s good to pair a conceptual topic, like force middle, with a

related skill like deep defense, to break up the monotony of discussing a

single topic for an entire practice. When planning practices, make sure to

note how much time you want to spend on each drill or scrimmage, then stick to

that time schedule during practice.

When teaching a new concept to your team, it’s important not to overload

players with information. Limit the voices in the huddle to coaches or the

person presenting the concept or drill, and make sure they stick to

emphasizing the key takeaways from the drill. While other players might have

advanced insight, it’s more effective to have them talk to the coach

separately, or talk to players individually instead of to the entire group.

Give the team two or three points to think about when doing drills - any more,

and it becomes too much to focus on.

A very effective teaching technique for drilling a concept or skill is to go

through several iterations of a similar drill, with increasing game realism.

Start with offense-only, or a 1v1 matchup, then move to adding more cutters,

more defenders, more active marks on the throwers, etc., until the drill

resembles an in-game situation. This builds muscle memory and helps people

realize how their individual motions fit into the offense or defense as a

whole. You can then move on to a scrimmage with a focus that makes the team

implement what they just learned.

It’s important to keep the entire team engaged during the whole practice -

veterans, rookies, and injured players. Limit downtime between drills, don’t

let people complain about drills, invent scoring systems for drills, and give

incentives. For instance, in a drill that works on the defense forcing out in

1v1 downfield defense, give the offense 1 point for catching a deep goal, 2

points for catching an in cut, and 0 points for a turnover.

Remember when planning practices: Do it in advance. Combine concepts and

skills for a themed practice. Limit the talking. Give a couple points to focus

on. Drill with increasing realism. Scrimmage with a focus. Keep the team

engaged.

Practice is where the biggest gains are made, and smooth, effective practices

are focused and planned in advance.

Shannon O'Malley

Elementary Ultimate (Ages 8-11) Beginners

Fun, fun fun.

When it comes down to it, these guys just aren’t quite developed enough to

hold attention on one thing for anything longer than 15 minutes. So first

things first, you really have to chunk your practice out. Secondly, these kids

are just learning how to use their bodies in an athletic way and ultimately a

lot of what you do will be teaching them overall coordination and control of

their bodies. Lastly, you are probably introducing this game to the kids for

the first time in the life, teach them to love the game make every minute

exciting and fun! Get them started with an activity that doesn’t even involve

a disc or involves it but not in a conventional way. (Tag, Capture the

Frisbee, Relay races with the disc as a baton).

Now that they are warmed up and hopefully a little bit tired, this would be

the time to teach them in their first chunk, whether it’s throwing, catching

or the basics on cutting you have about 15 to 20 minutes. The basic outline of

practice should alternate between a skill focused drill and a game that works

on that skill. It’s also important to remember when planning a practice for a

group of kids this age is to include an activity or game that really

emphasizes teamwork, sportsmanship, and spirit. Along with learning the game

these guys are still learning how to work with others and how to do it

respectfully in a competitive environment.

Favorite drills/games for kids this age

- Dog: two players run deep for a pass trying to catch it.

- Frisbee tag: players who are “it” work together to pass the disc around and tag others with the disc or by throwing a soft pass at another player for them to become it as well. Played in an end zone.

- Ladder drill races: team members must run ahead of the player with the disc and receive a pass to gain yards and make their way down the field. Players must throw and receive from the same player, teams of 4 or 5.

Potential Practice Plan 1.5 hours

- 0-10/15min: Warm up game

- 15min-30: Partner throwing/catching

- 30-45: Ladder relay drill

- Break

- 55min-1hr 10: Basic come to drill

- 1:15-1:30: Dog Drill

Middle School (Grade 11-14) Intermediate

This age can often be a tough group to plan a practice for. For developing

programs you may end up with a mix of kids some of which have never touched a

disc before and some of which have been playing for 3 years. Many of these

practices can be run with the same mentality as the Elementary level but with

more in depth and intermediate level skill work. For programs that are

developed with multiple teams you now have the option to really break the

practice into groups based on skill. It is still really important at this age

to be running drills that focus a lot on teamwork and sportsmanship especially

as the kids start to get more competitive and obtain egos.

On to planning, as a teacher I take every moment as a teaching opportunity

even if the kids don’t know it. Start off with a proper warm up, jog, stretch,

some beginning plyos. Teach them good habits for when they are old because at

the rate they are going they may not be playing past 25. From there it is

great to start with throwing because all players at this age especially need

it and it’s a great time to get your one on one in with the kids. Move on to

your first drill of the day, a nice warm up with some sort of game aspect to

it or challenge, even though they are older attention spans are still low. For

my older kids, 8th grade, I like to have two drills in a row come next

focusing on the theme of that days practice, the first breaking down the skill

and the second being an application of that skill in a real time situation. I

always like to end practice with a full scrimmage, they deserve it and really

these kids just need to play, play, play, have fun and learn to play as a

team.

Themes for practice at this level

- Fundamentals!: Footwork, how to cut, finding open space, proper throwing form

- Timing cuts off others, Offensive cutting patters, Vert or Ho stack

- Defense body positioning

- Marking and the Force

Practice Outline 2 hours

- 0-20minutes Warm up

- 20-30minutes Throwing

- 30-40/45minutes Warm up drill/game

- 45minutes -1hr first drill, skill focus

- Break

- 1:05-1:20 2nd drill - application, more game like situation than first

- 1:30-2hr Scrimmage, Game to 5

Tyler Kinley

1. Write it down.

This helps you remember your plan, creates a document that you can return to,

and can be emailed to the team beforehand if you feel it would help.

2. Specify time allotments for each segment of practice.

This creates a schedule, and is easier on you (you know when to start/stop a

drill) and your team (they know there’s a plan to stick to).

3. Don’t perform a drill for more than 15 minutes.

Attention spans are short. Realizing this, and not fighting it, is important.

However, running a drill for 10 minutes, then adding a new element/twist, can

allow for longer drilling on a certain skill while keeping interest level

high. Say, drilling a skill first without defenders, then adding a mark, then

adding full defense, can give three iterations of a drill over three 10-minute

periods while still changing it enough to maintain interest.

4. Allow for feedback… after practice.

Everyone’s a critic. When someone tells you how a drill should be run, or why

it sucks, remember that they want the same thing as you – to have the best

practice possible – and let them know that their criticism is valuable, but

best heard after practice is over, when you can spend time discussing how to

improve or add drills. Giving a critic the responsibility of planning a drill

often opens their eyes to how difficult running a practice is, and is a

valuable tool to getting them on board.

In addition, seek feedback from the team. Ask players what they think of

practice, what they want to work on individually and what they think the team

should work on. An “open mic” team meeting can often be a great means of

soliciting ideas for drills, for skills to focus on, and for team buy-in. When

a player sees the drill s/he recommended use at a practice, they are that much

more invested in the drill’s success and will show it in their own effort.

5. Let practice plans come from strategy meetings.

Assessing the goals, strengths, and weaknesses of your team as a whole can

often make practice planning seem easy and obvious, whereas before it seems

daunting and complex. Early season? Use practice time to assess your strengths

and weaknesses with ample scrimmage time. Mid season? Use early tourney

performance to guide what you need to work on and reinforce. Late in the

season? Write down everyhting you’d like to work on, then look at how many

practices you have left, and create a plan for what you most need to work on

and focus on that.

6. Feeling overwhelmed?

Ask for help. In many ultimate communities there are some really smart people

out there that would be both flattered and excited to help you out. Buy ’em a

beer and chat about what you’d like to do, and what advice they have for you.

7. You’ll be fine.

Planning a practice, then running it, are difficult, and can be scary. When I

helped plan and run drills for the first time as a second-year player / first-

year captain on Sockeye, I was nervous and felt out of my league. But, after

time, and after some successes and some failures, I realized what I could

offer and what I should and could rely on others to offer, and established a

place for myself as a practice leader. Being nervous means you care; don’t let

it prevent you from running great practices.

Jeff Eastham-Anderson

Epic rants by NBA legends

belittling the importance of practice aside, there is a wealth of evidence

that points to the importance of practice, both quantity and quality, when it

comes to improving athletic performance. Many people have noted that athletes

seem to require at least 10 years from the time they begin a sport until they

are able to reach the top of their game. Others have taken this analysis

further. Malcolm Gladwell observed in his book,

Outliers, that top performers

can only manage to practice effectively for about 1,000 hours every year, thus

arriving with the often quoted “10,000 hour rule” which must be satisfied in

order to master a complex task. Matthew Syed takes this observation a bit

further in his book, Bounce, by pointing out

that those practice hours must be purposeful, and filled with failure; simply

going through the motions and not challenging yourself to the point of failure

does not lead to sustained improvement.

What qualifies as practice is still a bit murky to me, but there are two

numbers to consider which helps put things in perspective. First, a 40-hour

work week equals about 2000 hours a year. To hit the 1,000 hour a year mark,

you need to be putting in about 3 hour days, seven days a week, for a whole

year. Second, some very sketchy calculations suggest that during my 13 years

playing Ultimate, I’ve logged between 5,000 and 6,000 hours on the field. I

think it’s safe to say that a vanishingly small number of Ultimate players

have to worry about practicing too much, or satisfying the 10,000 hour rule.

So, the question of how to get the most out of a practice is extremely valid.

For my part, I’m going to focus on four basic principles to keep in mind when

figuring out how to practice, along an example or two. It’s up to you and your

team to figure out how to apply them.

Get Everyone on the Same Page:

This goes without saying to a certain extent, and comes in a variety of forms;

playbook meetings, moving discs around on the ground, on-field examples, etc.

The team should be presented with concepts in a controlled setting where

questions are easily asked and answers are quickly given. Simply put, the

majority of this explanation should take place before your team warms up, or

at least after any substantial breaks during practice. Further, someone should

have spent enough time thinking about that concept to the point where they

don’t have to think about the answer, or consult the playbook.

Maximize your reps:

In a word, drills. The function of drills is to allow everyone on your team to

cement basic concepts and movements through repetition. Entrusting your team

to learn by just playing games is not sufficient. An entire game may only

present an individual player with a handful of opportunities to implement a

certain concept, while the majority of their time is spent between points,

watching from the sideline, or executing other concepts (hopefully) to

perfection; time which is not spent improving on newly learned concepts. The

drills don’t have to be perfect, but you definitely need to think about both

how best to convey the strategy you are trying to teach, and the logistics of

people moving through a drill in order to maximize the number or repetitions.

Additionally, consider making a substantial portion of your warm-ups for

practices and tournaments a drill your team has run recently.

Take it up a notch:

Once your team has the basics down, your drills and games need to be modified

to make things more difficult in order to push beyond your limits. This is

where the aspect of failure as an important aspect of practice comes into

play. Only by changing the set-up of your drills, or the rules by which you

play your games to make execution more difficult will you be pushed beyond

your limits to the point of failure. At that point, every failure should be

treated as a learning opportunity. Shortening the stall count to force moving

the disc faster, or a designated poacher on defense are just two examples, but

there are lots of creative ways to make things more difficult. Finally, there

should be sufficient downtime incorporated into a drill or game for people to

register mistakes, discuss what happened, and think about alternatives.

Follow it through:

During the course of a season, there are a lot of things to cover, and there

is an innate tendency for coaches and captains to assume that once a concept

is explained and executed successfully once, it is time to move on to the next

one. Remember, it takes 10,000 hours to “master” a sport, and the vast

majority of that is repetition. Concepts should be serially revisited, and

teammates held accountable for not carrying forward past lessons.

Anecdotally, two months is a ballpark amount of time you should allow for a

reasonably complex task, like a particular zone defense, or even a complex set

play. This comes primarily from my observation that of all the concepts

introduced after Regionals, at most one in ten was ever implemented at

Nationals.

Melissa Witmer

Practice planning isn’t just for the team captain. Every player should take it

upon themselves to have throwing practice in addition to team practice. Make

the most of your practice hours by incorporating these habits into your

throwing regimen.

1. Choose the right throwing partner(s)

Before you can even practice, you need a throwing partner!

Find a good throwing partner or several partners. If you’re serious about

becoming an all-star handler, you will probably need more than one partner to

get in the amount of hours required. Your ideal partner should also be on a

mission to become a better thrower. Your partner may or may not be your best

friend on the team. You are not going out to toss around and socialize. You

are going out to practice. You need a partner that shares this mindset.

The rookies on your team may be your best bet for a consistent, enthusiastic

throwing partner. If you are an upperclassman, they will be flattered by your

attention and less likely to bail on your scheduled throwing times.

Furthermore someone who is just learning to throw will be more likely to have

the insatiable appetite for throwing hours that you need. They will make sure

that you keep your throwing appointments even when it’s rainy or you just

don’t feel like it.

2. Warm up

If you want a quality session, it will be physically demanding. Killer low

release throws require a killer range of motion in your hips. Big hucks

require big time rotational forces at a high rate of speed. This is practice,

so treat it like one and prepare your body accordingly.

basic warm up sequence:

3. Choose a Focus Throw

While you will hopefully be improving all of your throws, I have found in

extremely helpful to have one particular throw that I am intent on improving.

The mind has limited resources and a limited ability to focus. Having one

focus throw will enable you to use those limited resources more effectively.

Your focus throw should be specific.

Not, “forehand” but “flat forehand.” Or “low release inside out forehand.”

4. Variation

One of the most important concept of practice is variability or practice. The

more variety the more efficient the learning process will be. Instead of

throwing 20 of the same exact throw in a row, you will learn better if each

throw is different from the one before it. This is counter-intuitive, I know.

But it is one of the most robust finding of motor skills research.

So how can you have a focus throw and still have variability in practice? I

recommend breaking up your focus throw trials with other throws in between.

You could throw three low release backhands, two forehands, three low release

backhands, two high release backhand, three low release backhands, two

hammers. Using this method, you will still have more trials of your focus

throw while still having variability and minimizing the effect of contextual

interference.

5. Visualization

Have a crystal clear picture in your mind of what you want your focus throw to

look like. Many of my signature throws are based on the throws of others. It

can help to have a model in mind. Pick your favorite handler. Do you like

their low release backhand? See if you can replicate it. The throw will, of

course, end up looking slightly different because everyone’s body is

different. Still, having the idea in your mind of what you want your throw to

look like will help.

When you’re throwing visualize the trajectory of your throw. Just as you’re

being specific with your focus throw, be specific in visualizing the

trajectory you want. How much angle? What velocity? Where are you hitting your

target? Visualize the trajectory you want before each and every one of your

focus throw trials. With practice this will become second nature and not take

any extra time. Don’t spend too much time thinking, the visualization is a

millisecond snapshot or film clip of the throw.

6. Have a pattern to your practice session.

This is what mine looks like:

- warm up

- mess around for about 5 minutes with whatever throws you feel like. (This is part of your warm up.)

- Get to work. Focus on the details. This is the time to work on any biomechanics you are trying to change. This is the most mentally challenging part, so we do it early while our focus is best.

- Conditioning. Here is where you want to get stronger in the motions that are specific to throwing or just gain some endurance. Throw harder, faster fakes. Throw longer throws. Do some give-n-go drills with your partner.

- Cool down. Decompress. This will often happen naturally when you reach the point of mental fatigue. This is when you’re allowed to throw your silly throws. Socialize a bit with your throwing partner and leave the field happy so that you want to come back for more!

7. Know when to stop

As I’ve said, the focus of the brain is a limited resource. Engaging in

deliberate, focused throwing practice is work. Eventually, your ability to

focus will wear out. Don’t fight it, accept it. If you start feeling

frustrated, you’ll become tense and your movement patterns will be affected.

Frustration also prevents objective evaluation and adjustment of each trial.

If you cannot recenter yourself, it is best to stop and try another day. As

you gain experience with throwing practice you will naturally gain a better

feel for when you are mentally done.

How long this takes is the length of your throwing sessions will also be

influenced by your level of conditioning. If you aren’t used to lunges, your

legs will wear out before your brain. Your shoulder can also wear out quickly

if you do too much hucking too fast. For learning motor skills, the more you

do the better. However, you still need to respect your physical limitations.

Start with shorter sessions and build up to longer ones to allow your body to

adapt.

Final Thought

Putting a large chunk of time into throwing practice early in your career will

have a huge impact on how it unfolds. Fitness can come and go but motor skills

stay with you for life.

John Korber

Practice is a vital part of mastering any skill, and team sports are no

exception. A quality practice structure can transform a meaningless few hours

running around into a valuable and productive growth opportunity for your

team. While the content covered in a given practice clearly varies heavily

with the level, division, weather, time of year, etc, some of the basics of

running a quality practice are nearly always applicable. Here are a few of my

favorites.

Know your audience – The frequency, duration, content and tone of your

practice should be specifically catered to your audience. The team’s physical

condition, level of experience, or even individual maturity can impact what

you can cover and for how long. Your group of seasoned club veterans will

probably have some patience for 15 minutes talking about the subtleties of a

zone defense; your brand new group of high school rookies probably needs a

shorter, more simple presentation.

Have a purpose for everything you do – Demand of your players (and

yourself) that anything worth spending time on should be for a good reason.

Structure your practice with activities with particular purposes…generally the

more specific the better. Share the goal with the team and make it a clear

objective. Clearly measurable actions are often the easiest for everyone to

keep track of. For example, this year my team was struggling with moving the

disc horizontally, so we would scrimmage and limit the offense to 4 throws

without crossing the vertical midline of the field. Failure to do so resulted

in a turnover. Players on the sideline counted the throws out loud to make

everyone aware. The specific, measurable objective quickly opened up our

offense and got us comfortable moving the disc horizontally.

Success: crossed midline within 4 passes

Turnover: failure to cross within 4 passes

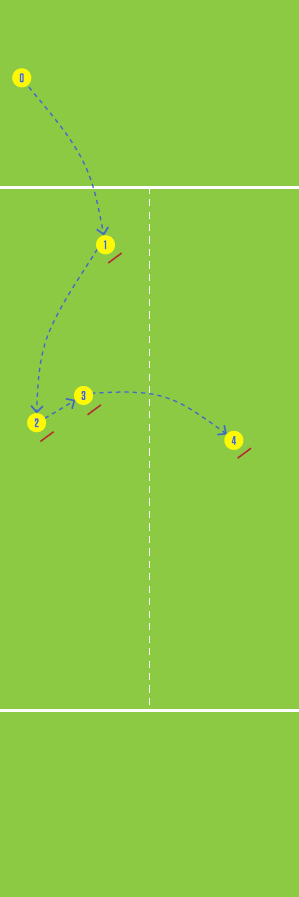

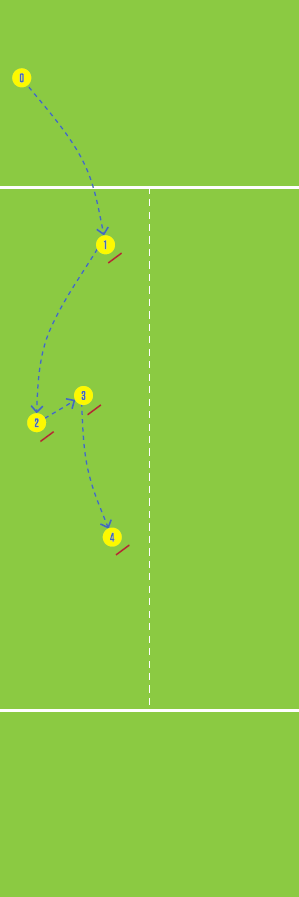

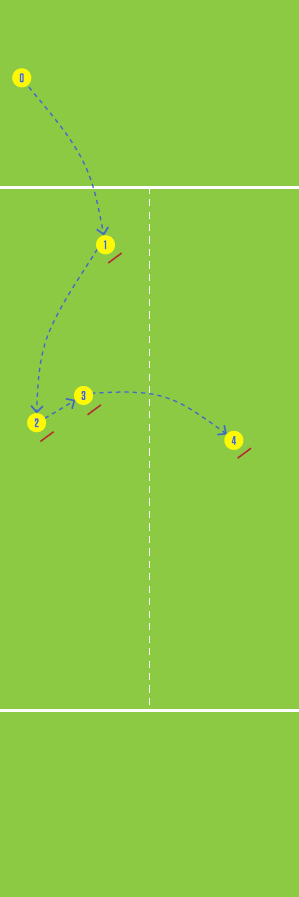

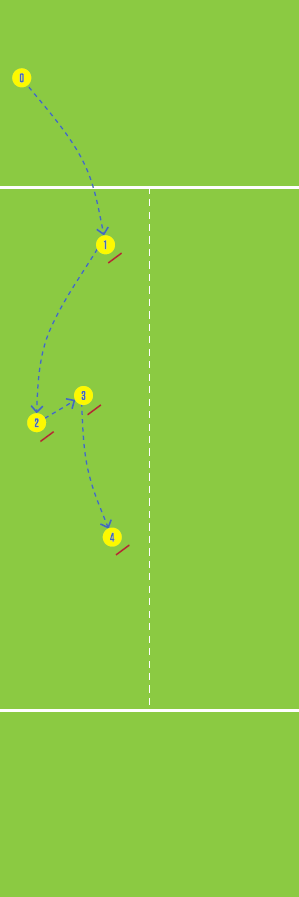

[Diagrams by Kathryn Irons]

Keep things moving – Regardless of the demographic of your team, learning

is often best facilitated with variation. Keep your drills short, 10 to 15

minutes maximum. The result of the drill is not as important as the

experience. Sometimes letting the team struggle with a new concept and work it

out is for the best. Succeed or fail, after 15 minutes most drills get stale

and it is time to move on. Take water breaks as a team between segments of

your practice, and encourage players to push through the current segment

without stepping aside for rest. It is much easier to demand a high level of

focus for short spurts than to ask your players to stay with you for hours in

a row and self-regulate their attention.

Mind your distance – Teaching and learning is a personal exchange between

teacher and student. When it is time to teach, explain, or diagram a concept,

bring the team in close and talk so everyone can hear you. When an individual

player requires feedback (not to be confused with encouragement), have a

conversation instead of yelling across the field. When it is time to practice

what they have learned, let them play. Keep your distance and let them

experience what they need to. When it is time to teach again, reel them in for

a water break and go back to the chalkboard.

Keep up the intensity – While walkthroughs and careful demonstrations are

an important part of teaching, learning and developing muscle memory almost

always needs to be done at game speed. Ultimate is played best in short bursts

of energy, much more like hockey shifts than a soccer game. Practice is the

time to develop comfort with the repetition of explosive output while

mastering the poise of executing fine motor skills at that level. If the

intensity in your practice exceeds the intensity of any game you play during

the season, you are preparing your team well. To allow your players to go

through the motions and use excuses like “In a game I’d layout for that,” is

doing them a disservice.

Ben Slade

It’s the end of the day, and it feels like nothing has been accomplished.

Teammates barely listened to instruction, drills were sloppy and unfocused,

everything took twice as long as it should have, and you walk away with a sick

taste in your mouth, directing your anger and frustration towards the most

vocal trouble-makers. That’s right, you’ve just experienced another bad

practice.

We’ve all had this feeling before, and while you’ll probably have it again,

there are ways we can reduce the severity of the bad practice. I think that

there are three main enemies which can subvert your practice time and cause

your players to lose focus, and they are all (partially) under your control.

These three problem areas are poorly chosen drills, lax leadership, and too

much wasted time between activities.

First things first. If you are a college or youth team, odds are good that

there are not enough Frisbees in the air at practice. Many drills are ill-

suited for your needs, and they all revolve around the same theme: two (or

more) lines, one frisbee, and lots of players watching a single actor while

waiting for their turn. This is exacerbated 1) for clubs that are large or

almost big enough to split into two teams, and 2) for clubs that share

practices with their B team due to time/space considerations.

Actively campaign to maximize the “touches” each player gets in a single

practice, especially early in the season. Split “line drills” in half or in

thirds to increase productivity. If the drill requires a lot of space, combine

it with one or two compact throwing/running/catching drills, and rotate

players every 15 minutes. If you have 25+ players and limited space, consider

building four or five 3 v 3 fields (30x20 w/ 5 yard endzones) perpendicular to

your field instead of a single scrimmage. Invent drills that let you move in

‘waves’ across the field, then sprint back to the beginning, so that discs are

always in the air. Split your team into thirds and have 2/3 scrimmage each

other or play endzone games while the other third runs a drill, and rotate on

the clock. Always be pushing to get more discs and people moving, and it will

translate into confidence when it matters.

Regarding lax leadership: this should go without saying, but if you wait until

everybody shows up to start practice, you are doing your team a terrible

disservice. As a player, you should ask your friends to come 15 minutes early

to each practice to “help you with your throws,” and, as a captain, start

running warm-ups in the first minute of your scheduled practice time. If your

leaders are late, your team will be late. Always. Elect punctual captains.

Elected captains: create a culture of earliness and refuse to start practice

late.

Finally, if you want to reduce dead time in between drills, you need to always

tell your players the next thing that they will be doing. You can minimize

that awkward dead period in between drills by planning ahead and by giving a

defined break time (e.g. “90 seconds to get water, then we are doing a 3-man

breakmark drill”). Captain-coaches, this means that you have to duck out of

the present task five minutes early to set up the next drill. If you are lucky

enough to have a coach, encourage him or her to take care of it.

If you can get more discs in the air, make use of your full practice time, and

always tell people where and when they are headed next (and have it ready for

them), you will be amazed at how much more productive your practices are. In

my experience, players are generally motivated to work hard, and will exhibit

good practice attitudes if you keep them busy and keep them moving.