(This past week for the first birthday of The Huddle, Kirk Savage got

us a present...Al Nichols' article about layout blocks. Kind of like

reading about 'Playing well in the 4th quarter" by Larry Bird. Thanks

to everyone that has supported us all year!)

You've trained, you've watched film, and you know your opponent. Maybe

you've been waiting all game, all season, or your entire Ultimate life

to take a layout block from that player in a big game. Like hitting a

walk-off home-run. Like marching around your hometown with the Stanley

Cup in your Radio Flyer.

Many mediocre players spent many hours visualizing these outcomes. The

best defenders, though, try to understand the process that can get you

to that block. How should you plan to create block opportunities? Where

should your feet be? Your core? Your arms?

Your mind?

We asked our authors how they play this situation, and how they think

about it themselves both as a player and a coach. Enjoy.…and then go

get some of your own!

Adam Goff

I don’t remember ever thinking “It’s time for a layout block” or “I need to be

in a position to get a layout block on this throw.” My goal was simply to be

in the best position I could be in to cover the person who was my

responsibility at the time. I believe that layout blocks are simply

‘opportunities taken’—being in the right place at the right time, and the

offense made just enough of a mistake for you to go get it. However, there are

a few situations where simple choices can put you in a slightly better

position for that elusive layout block. I’ll describe one of the common ones

here.

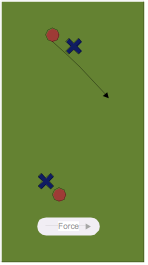

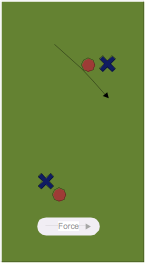

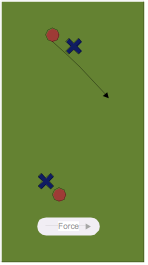

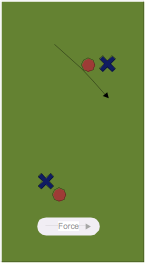

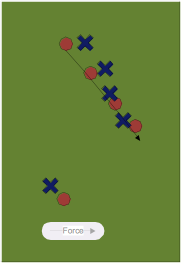

Defensive positioning is often about angles. As the defender, you want to own

the better angle to the disc after it is thrown. So, here’s the situation: You

are covering an upfield cutter who makes a cut on an angle towards the open

side of the field, as shown in figure 1. This cut does happen in both vertical

and horizontal stacks, although the angle may be less when the cut is in the

horizontal stack.

As the cutter makes the cut, you the defender may become increasingly out of

position. You’ll be on the outside of the receiver and then the receiver owns

the angle.

Many of the layout blocks that I’ve gotten, have been in this situation.

Instead of staying on the outside or trying to stay in front of the receiver,

I slide back a step and take the inside. I do this after the angle of the

throw gets to be to the receivers advantage if I stay on the ‘force side.’

When the throw goes up, you the defender are now in position to make that

layout block—you own the angle. The same theory applies to other situations on

the field.

Brett Matzuka

This is a skill that many of the top defenders possess which generates lots of

lay out blocks. There are 3 key components to a successful baited block.

1. Knowing the offense (thrower/cutter)

To many, this is just knowing how far away you can let your player get before

you can’t make up the ground in time to get a bid on the pass. Knowing how

much ground you can make up on your player when the disc goes up is the most

important part to knowing the offense; if you can’t regain the ground when the

disc is thrown, you surely won’t get the block. However, also knowing the

current offensive circumstance and the thrower will be the icing on the cake.

A good thrower is patient and confident with the disc and will look off an

even slightly questionable pass for another option, or if they choose to throw

it, are more likley to place it far enough away to prevent the opportunity for

a bid. An average thrower, however, will be more likely try to unload the disc

quickly, which should give you the opportunity for the baited block. Other key

factors to consider are: Did the thrower just receive the disc with a zero

count, or is the count high? are they trapped on the line or at center field?

Is the there offensive flow currently or not? All these questions will have a

big affect on whether the bait and bid is successful, or whether you may

overcommit and expose your defense to a devastating blow.

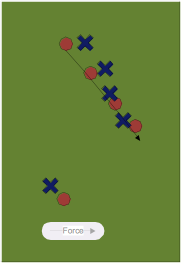

2. Be on your toes (literally)

If you are baiting for a block, be ready to actually get the block. Too many

times a defender has given up a few steps unintentionally, sees the impending

throw to their man, and actually manages to make up the ground but doesn’t get

in position to convert the block. To turn this from a run past and expose your

defense to an unmarked man to a lay out D, you have to prepare a few steps

before you are within striking distance. Simply put, when you are 3 to 4 steps

away from making a play, get low and maximize the amount of spring you can get

from your legs, (much like a lay up in basketball) take your 2-3 short step

routine to prepare to explode, and then execute. If you don’t prepare to bid a

few steps before, it will pass you by.

3. Desire

This sounds cheesy and much like a cliche, but it is honestly the truth. You

can have both of the above and still not manage to get the block. This last

part completes the package. You give the offensive player enough steps to look

like a viable option while still maintaining enough distance to make a bid.

The throw goes up and you make up the ground while preparing for the bid by

getting low and going through the lay out routine. However, if you lack the

passion, determination, or desire, you will hear a lot of people

congratulating you on a nice bid, and just that, bid, not D. Desire here isn’t

just defined as your thirst for the disc, but as the focus and attention to

any inconsequential detail or deviation that might potentially prevent the bid

from becoming a block. That millisecond that you explode horizontally into the

air, you have to be so focused and hungry for the disc that you keep your eye

locked onto the disc (where it is going, where the offensive player plans to

catch it, etc.) and position your body, limbs, and hands in a way to

deflect/catch the disc while accounting for any deviation from your initial

preparation that has occured along the flight path. This, simply put, is

desire. Not letting any hiccup prevent you from making your lay out eventuate

into a D.

If you can manage to learn these 3 components, hurling yourself through the

air will be the easy part that puts the icing on the cake.

Tully Beatty

D, they say, is for dummies. But no D player worth their salt should have the

ability to do anything more than stare at their big toe Saturday night at the

hotel. Why? Because they should be too mentally taxed from keeping the stall

count each time they step on the field for D. I’m not talking about counting

the stall when marking your assignment; I’m talking about keeping the stall

when playing D in the stack or spread. Any O player doing the same thing at

stall 4 and stall 8 is giving their defender at chance at the grail. Of course

you can’t do it every possession of every point of every game early in the

series and you shouldn’t need to do it you’re a 1 seed facing a 16 seed, but

by the 3rd round at sectionals, it’s time to say goodbye to Mickey Mouse

Frisbee and work yourself into a mental lather; and if you’re on a team that

demands up-calls and a vocal sideline, then even better for you. Obviously

it’s more difficult when defending the spread, but if you bide your time and

sit on a team’s offense long enough and other defenders are digging in, you

figure the O out and sometimes you get the grail, other times you see yourself

in its reflection.

Hard to believe it’s almost been ten years, but my wife’s block vs RFBF in the

‘99 Mixed finals is the best layout block I’ve ever seen. The block earned her

a concussion and the Llama a trip to Germany [and recently I read where

someone said Mixed is for pansies]. A deep shot was sent to the girl she was

guarding but Matt Hull leaped a got a finger on the disc, deflecting its

course and Amy was able to come back under, layout and knock it down,

simultaneously taking a knee to the back of the head and getting knocked the

hell out.

On a lighter note, at Fools one year, I saw KD, after shot-gunning not one but

two beers during a time-out, get a layout block on a dump pass that was thrown

by the guy he was marking. The pass couldn’t have gone two yards before he

blocked it. It was pretty sweet.

Al Nichols

In the perfect defensive scenario, no one ever has to get a layout block. The

marker does a great job of taking away part of the field and preventing hucks.

Lane cutter defenders deny any open space to downfield receivers and when the

count is getting higher, the dump defender stuffs the reset option. The

thrower is left with nothing and quietly puts down the disc after hearing the

word ten. How often does that happen?

I think most teams and their defensive players are not attempting to get a

block on any given point but rather trying to prevent their opponents from

getting open enough for a high percentage pass. Relatively easy to do against

opponents who struggle to throw it long or to break the mark but increasingly

difficult with better throwers and receivers. Against stronger throwers and

receivers the defender is forced to position themselves closer to their

opponent and as a result you often find yourself chasing someone as opposed to

dictating to them where they can go. Most layout blocks come about from this

position, where receiver is in full flight to an open space, a step or two

ahead of their defender, and the only defensive play left after the disc is up

is a layout bid. I’ve always found that there are three parts to making the

play: put yourself in position, seize the opportunity and a small mistake from

the offensive players.

Positon

The reality for most defenders is that you have to make a wide variety of

positional choices throughout a point, slightly altering these choices

depending on the team defensive strategy of the point, where the disc is on

the field, what the count is, your direct opponents strengths and weaknesses,

weather conditions and if you have time to check it out, the throwing

abilities of the person with the disc. But most of the time, in a man

defensive scenario, I’ve always lined up about a step on the open side of the

field and a step closer to the disc. If your receiver goes long or to the

break side of the field they’re already a little open without even having to

get you moving and you find yourself already chasing behind the receiver.

Though these passes are slightly higher risk, against good throwers the

defender has to bite on these cuts and try to stay as close as possible, so

when a receiver cuts back to the open side you will still often find yourself

chasing a receiver into the open side coming back to the disc even though your

initial position was to deny that particular cut. Defenders often find

themselves chasing receivers, offense dictating to the d, where the action is

going to take place. Fortunately, if you going to get a block against a good

thrower they usually have to see the receiver break open or the throw doesn’t

go up. But to get the block you need to have that opening be as small as

possible. Too close and the throw doesn’t go up, but hey great d. Too far

behind and you’ll never make a play, just get ready to start marking. But

about one step off the pace and you’re in position to maybe make a play.

Opportunity

Whenever I’ve been in the zone defensively and we’re playing a lot of man d, I

am able to put myself in the defensive position of about a step behind my

receiver consistently all game. And the moment we break into open space I’m

already hoping for a throw with every intention of laying out and making the

d. It is already in my mind. The timing of a layout block is critical and if

you’re not ready to dive it’s probably too late. Almost all high-level-

experienced players will lay out to catch the disc on O. The disc is right in

front of you, the expectation of everyone on the field and sidelines is that

you will at least try a layout if it is necessary. On D there’s no guarantee

that the throw will even go up, that if it does you will necessarily have a

shot at the disc but you have to assume that there’s going to be an

opportunity. You’re never going to get it by going around the person behind

them, so you have to figure out when and where you’re going to go inside his

trailing shoulder, without making contact. These are the two major steps in

seizing the opportunity: be ready and willing, and find an angle on the inside

the receiver between him and the disc.

The Mistake(s)

If you’re way faster than your opponent then when the throw goes up, blow by

your receiver and lay out or just catch it. For most players speed is fairly

even.

To get the block, no matter how well positioned and how ready to lay out you

still need a mistake.

Mistake#1

If a thrower reads his receiver’s position and speed relative to the defender

and throws it perfectly out in front of their teammate to run onto with arms

extended, the defender has no play. Get ready to mark. But if they throw it so

the disc is going to arrive right into the receiver’s body, maybe you’ve got a

chance. Being only one step behind and launching with arm fully extended

should make up the gap and give you a chance to catch or tip the incoming

disc. (I’ve always favoured launching and landing on my side for both comfort

and efficacy because reaching with one arm will give you an extra few inches

that could be key. I think it’s also more likely to avoid contact.)

Mistake#2

Even if the thrower misses his angle by enough of a margin to give you a

chance for a dive block, a smart receiver can change his angle to protect the

disc. Instead of continuing to run at the angle he initiated, when the

receiver sees the disc is going to be a little behind him or at his body, they

should make a more direct line back to the thrower to protect the disc. This

cuts off the defender’s angle and forces them to not lay out or if they do

it’s almost impossible to avoid contact. Fortunately, a lot of receivers think

they are more open then they are and will continue on their initial line. Run

softly.

Jeff Eastham-Anderson

Two key factors of getting a block are:

- Being able to recognize mistakes by the offense

- Being in a good position to capitalize upon them

Being faster than the person you’re guarding helps, but paying attention to

these two aspects will help your team defensively.

When it comes to positioning, as a defender I rarely bait throws in

anticipation of a layout block, especially when it comes to cuts that are

close to the disc. There is so little time to react, that my defensive goal is

to deny the throw. It just happens that the position to deny those kinds of

throws (even with or trailing the offensive player slightly, on the side

closest to the thrower), also allows for the occasional layout attempt. If you

are directly behind, or on the wrong side of the receiver, layout bids become

more difficult, and can be very dangerous to everyone involved.

Recognizing when the offense makes a mistake is the other key factor that

determines whether or not you should make a layout attempt. For the majority

of layout blocks I get, I knew when and where the disc was going to be thrown

at the same time as, or earlier than, the receiver. Being able to look

directly at the thrower, and keep the receiver in my peripheral vision gives

me equal footing when it comes to making a play on the disc. Alternatively, if

the receiver is making a one dimensional cut (i.e. the disc will be thrown to

them at point X, or not all), this also lets me get into a good defensive

position, and ready to make a bid.

Once the disc is in the air and I’ve decided I’m going attempt a block, if my

positioning is good I can choose the best line to take to get to the disc

without having to worry about what the receiver is doing. Whatever line the

receiver chooses, the defender has a bit of an advantage here as they do not

have to actually catch the disc. The slightest tip with a finger, or the mere

presence of your body, is sometimes good enough. The only real insight I have

on execution is that I try to drive off of the last step I take, just as I

would if I was jumping in the air. Just because you’re running as fast as you

can doesn’t mean you should stop running and fall forward in the hope of

getting a block.

I’m not really sure how you learn the body motions to successfully make a

block. Certainly there is timing involved, and landing in a controlled manner

is a plus. A high-jump mat, or sand pit would reduce the wear and tear, but at

some point you’re going to have to graduate to the hard stuff. As I mentioned

above, drive off the last step you take. The primary impact should be taken by

your abdomen hitting the ground as flatly as possible. After every practice

attempt, get up as quickly as possible and set an imaginary mark. Not every

bid is successful, and you will have set the mark if you miss.

Ted Munter

Ah the layout block, the play that got you started, the one you still dream

about, the slam dunk of our game. Or maybe the three-pointer.

On a bad throw everyone can get what looks like a good block. That’s why you

play summer league. But when teams are executing well, coming up with a piece

is tough. Don’t over-commit to laying out or you will end up getting burned on

jukes and lying on the ground as the person you are supposed to cover has a

free throw.

Which is to say that layout’s, like all blocks, come from team defense. If

everyone is always going for a layout block (like everyone heaving up three-

pointers) each player might look good once and a while, but mostly you will

have a bunch of teammates playing as individual, not applying pressure as a

team.

So don’t just count on your best players to get blocks for you. Your top

defenders have to cover top O players and O has the advantage. Great defenders

play well within a team concept—forcing deep, forcing out, whatever—and set up

their layout blocks within that concept. They know that most offensive players

have a few pet moves. If you can identify them, you have a better chance of

getting a block. But players today are too athletic to bait. Let your team

bring pressure; you make the play when it comes your way. Unless it’s summer

league, your block should be the play everyone celebrates because they all

helped make it happen—even if you get the glory.

Adam Sigelman

Like all things holy, the more you try to explain it with words, the farther

you get from its essence…

Look: If you are on the field and thinking about getting a layout block,

you’re likely not playing good defense. I don’t think there is a recipe for

getting a layout block . I suppose you could practice, and I have seen people

working on their diving and landing techniques. But it also requires a

tremendous amount of luck.

First, the thrower has to make a decision that throwing to your man is the

best option. This point sounds obvious, but it’s important to recognize. It

means that for whatever reason, the throw either yields a big reward compared

to the risk of turnover, or the thrower miscalculates and thinks the receiver

is more open than she is. Let’s say you are the best defender on the team and

consistently smother whoever you are guarding. You will end up with no layout

blocks if the throwers always look off your man. How many layout blocks you

get should never be the barometer of the quality of your defense.

Second, the thrower has to make a bad throw. Perhaps the throw is a little too

far on the inside, or floated a little too long. Whatever happened, you had

the time to hurl yourself at it and get a piece. But if you blocked the throw,

it should have never been thrown or it should have been thrown better. Good

throwers and cutters know this. If you are thinking “layout block” and baiting

a throw, they will make you pay by either putting the disc out to space where

you can’t get it or throwing a pump fake and hitting your man going the other

way.

Here’s my advice for getting layout blocks, both for individuals and for

entire teams. Play hard-nosed, take-no-prisoners defense. Follow the

guidelines for effective D that have been enumerated many other times

throughout this blog and elsewhere (dictate, triangulate, limit the cushion,

use your body, etc.). Get in your man’s shorts and deny the disc, beating her

to every spot. And then, when the thrower does make a mistake (and even the

best will on occasion), you’ll know what to do.

Greg Husak

I’m frequently torn between the value of a layout block versus just shutting

your guy down to the point that he’s not thrown to. Layout blocks, at least at

the elite level, are typically the result of a bad decision or throw by the

thrower, because it is very tough to get around elite receivers, and you’re

generally just not going to make up enough ground to go from a guy being open

to you blocking him unless the throw is in a bad spot or the receiver does a

terrible job of sealing you. That being said, I think there is definitely an

art to putting yourself in this position so that when the opportunity comes

you can take advantage.

The primary factor is desire. Whether it’s the desire to keep your guy from

getting it, to get the disc or win the glory of making that play, something

has to be ticking in the defender’s head that will make him hurl his body at

the disc. Learning the game in California we would occasionally work out and

play on the beach where the potential for injury dramatically decreases and

you start to think that maybe that’s possible on grass too. However, despite

training and practice, at some level the layout block is an uncontrolled

action with the prime motivation to get the disc. The mind just has stay out

of the way and let the body do its thing.

I’ve seen a lot of great blocks in big games, many of them for or against the

team I was playing on, which can bias me. However, one that I saw early in my

career, at my first nationals, is one of the few I remember that didn’t

involve my team. It was Boston DoG, and I believe it was their epic semifinal

of 1997 against Ring of Fire. Boston pulls during their epic comeback (they

were down like 7-1 to start the game) and one of the markers in their

clam/zone is sprinting down and the first pass is about to get thrown right by

him. As he’s sprinting he somehow launches his body at a nearly right-angle to

his left and about chest high. I actually cant even remember if he got the

block, but I know it was a super-human effort for a pass that, while it was

his responsibility, wasn’t really to his man. As he came do the ground he

didn’t get up and the word was that he tore his ACL, or something in his knee.

Boston went on to win that semifinal, and ultimately take down Sockeye in the

final.