Adam Goff

The key goal when receiving the pull is to get into your play/offense as

quickly and safely as possible. A few thoughts on how to do this:

Unless the pull is going out of bounds or a big blade in a nice wind, catch

it and get it moving. If it’s a big blade, stop it as soon as it hits and do

the same thing. The only situation which I can think of in which you would not

want to do this is if the pull is going to hit and slide out of bounds AND the

defense is already set up on all the people you might throw to. That’s pretty

rare, so get it going.

If you are trying to get the disc to the center of the field (common in a

horizontal offense), then it is a good idea to have that thrower start near

the middle of your line on the pull, and the other two handlers lined up near

the outsides. That way either one of them can receive the pull. As soon as it

is determined who will receive the pull, the other handler must get into

position so you have options. The defense, especially if they know your

team, will work hard to stop your first option. You need the second option,

and sometimes a third option. Just having this first pass option is not enough

— you need to have an ability to run the play or your offense off of this.

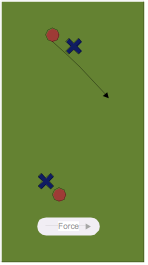

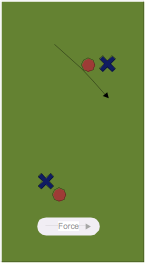

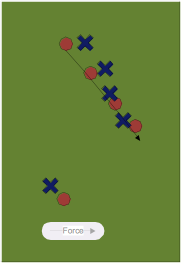

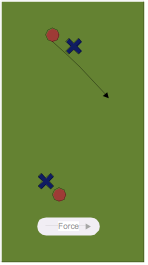

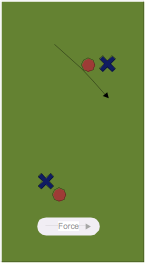

One special option: We used to call this “X” and it would be called after the

pull. If the pull was deep, and especially if it was windy and we were going

upwind, the ‘option handler’ could call “X.” This means that the option

handler would receive the first pass and then pass it to the person who was

supposed to receive that pass. This let us take two passes to move the disc.

It’s a good option when the defense isn’t covering quickly or when you are

worried about the wind.

Your upfield players must get into position quickly. If they do this, you

are basically already running your offense. You may define a first set that is

different from your flow, but it is still key to get into it. If even a single

player lags behind, that’s one defender who can mess up the works.

Have a language. There should be clear communication as the pull comes in.

Define who will say what and exactly what that person will say. For example,

some teams will choose the side of the field to attack while the pull is in

the air — if so, know who is calling that (is it the person to receive the

first pass? the option?), know what to say (if you say “left” which side is

that?), and know what the options are. Even just saying “You got time” makes a

difference. The pull receiver can then think about one thing — catching the

pull. When calling the offense/positions before the pull, it should be known

who says what.

Get some yards, but don’t stress about it. Try to get some yards on the

first pass, but it is more important that this is a good, safe pass. There is

no reason to push this one and try to get too much. This will dictate your

setup. Your up-field players should plan to set up based on where the person

receiving the first pass will be. This means that person needs to get to this

spot quickly. The location will depend on the quality of the pull and the

speed of the defense. I would also suggest that this person plan to get to a

spot and then move back towards the thrower a bit. That gives a little more

leeway for a mistake on the throw — that first pass can be harder than you

think.

Look! Never marry a setup. Look at the D.

Adam Goff

Nothing earth-shattering here, but first and most important: the easiest way

to get out of this situation is to avoid it. A good offense recognizes what

the D is playing early (see the zone, see the clam, see everything). An anti-

reset mark can be set up by the defense several throws ahead. A person sits in

the lane, leaving the handler on the sideline open. It’s an obvious throw. The

first way to avoid this is to have that receiver (the person who would be

trapped) move towards the thrower. Often it is better to all but hand the disc

to this person, avoiding the longer throw and the trap. Even better, the

receiver can circle behind — resetting the count while moving upfield.

The second way to avoid this is to break the mark before you have to. When the

defense drops the person in the lane, don’t be tempted — work the disc the

other way.

Sometimes, you just can’t avoid going into the trap. In this case, I recommend

shortening the count in your mind. If you like to look reset or swing at 6,

then you are now thinking of doing it by 3. This often will help you get the

disc off prior to the mark getting set. A side note — it’s important that the

other players recognize that you are doing this — you need them to be looking

for the throws quickly. This doesn’t mean that you should panic. I’ve coached

teams to think of this situation as “three looks.”

Look 1 — you receive the disc and you start to turn — looking upfield and

back to the middle. Your first look is back into the field, away from the trap

sideline. Your priority is to gain yards, but avoid the trap.

Look 2 — you continue to turn — looking almost straight up field (close or

far).

Look 3 — you look back into the same place as look 1. You basically have

bounced your turn off of the sideline. Always looking upfield.

Adam Goff

There are a few key tricks that I have found make an effective mark. Some are

commonly talked about and pretty well agreed. I do think that not all of these

are universally agreed. This is mostly a list of key points, rather than in

depth on each one.

The first is mental. It’s very easy to relax when you get to a mark. It’s

important to remind yourself that you are responsible for more of the field

than any other single defender on the field. I see players lose this focus at

the biggest points in the biggest games. There’s no trick to this: you simply

can’t relax when you are marking; any good thrower will recognize that you

have let down your guard. The more intense you are, the better your mark.

Sidelines can be key in this. Get on the marker—provide information about

what’s going on, but don’t just let the marker relax. This isn’t the time

rest.

The second is also mental. As a marker, you cannot do everything. Do not try.

It’s very easy at the highest levels to start to think you can do more than

you can. The downfield defender that spends too much time worrying about other

players usually gets beat. The same is true for the marker. If you worry about

trying to block the thrower from getting the disc to the whole field, you will

likely not stop anything. You will be at the mercy of the throwers fakes. I

usually tell players that you can stop 90° of the field, and you can harass

throws in a little more (maybe 45-60° more). But you cannot stop a good

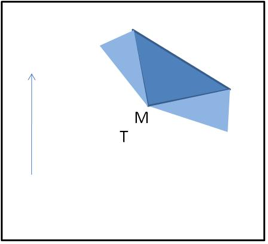

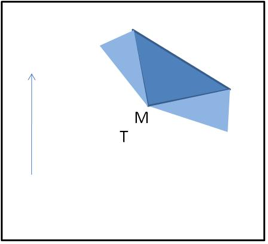

thrower from throwing into even half of the field. In the diagram, T is

thrower and M is marker, and the force is backhand. The dark blue is the area

that you should block—definitely. You should try to harass throws in the light

blue, but not at too much risk to your dark blue area.

Figure No. 1

Figure No. 1

The third is positioning. I believe that most marks, even at all but the very

top levels, are too far away from the thrower. It seems to be common practice

to back up when there’s a risk of, or experience with, getting broken.

Typically, movement (being on your toes, bouncing with the thrower pivots)

does a better job of keeping you from giving up that throw. It’s important to

have good balance and body position (arms low, knees over feet).* As a rule, I

try to be about 18" to 2’ from the thrower. Sometimes even closer. This is a

change from what beginners or even intermediate players are taught, but it’s

critical throughout.

The fourth is mental—again. As a marker, I want the thrower thinking about me.

I know that I am rarely aware of the marker when I’m throwing. When I’m not

aware of the marker it makes me very, very comfortable. Since I don’t want the

thrower comfortable when I’m marking, I will change things. I will change the

volume I’m counting. I will vary my distance a bit between stall

counts—shifting forward and back, and between marks. I will sometimes move my

arms more and sometimes less. I’ll yell different things to the defenders

around me.

* Zaslow and Parinella wrote a great guide to marking in “Ultimate Techniques

and Tactics.” Balance and arm position is key in this—I’d suggest giving it a

read if you haven’t. I didn’t cover items like balance, arm position, or

impact of field position. It’s covered very well in their book.

Adam Goff

I don’t remember ever thinking “It’s time for a layout block” or “I need to be

in a position to get a layout block on this throw.” My goal was simply to be

in the best position I could be in to cover the person who was my

responsibility at the time. I believe that layout blocks are simply

‘opportunities taken’—being in the right place at the right time, and the

offense made just enough of a mistake for you to go get it. However, there are

a few situations where simple choices can put you in a slightly better

position for that elusive layout block. I’ll describe one of the common ones

here.

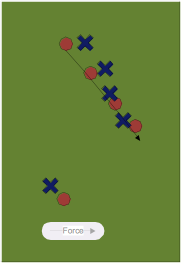

Defensive positioning is often about angles. As the defender, you want to own

the better angle to the disc after it is thrown. So, here’s the situation: You

are covering an upfield cutter who makes a cut on an angle towards the open

side of the field, as shown in figure 1. This cut does happen in both vertical

and horizontal stacks, although the angle may be less when the cut is in the

horizontal stack.

As the cutter makes the cut, you the defender may become increasingly out of

position. You’ll be on the outside of the receiver and then the receiver owns

the angle.

Many of the layout blocks that I’ve gotten, have been in this situation.

Instead of staying on the outside or trying to stay in front of the receiver,

I slide back a step and take the inside. I do this after the angle of the

throw gets to be to the receivers advantage if I stay on the ‘force side.’

When the throw goes up, you the defender are now in position to make that

layout block—you own the angle. The same theory applies to other situations on

the field.

Adam Goff

In a person defense, getting the right matchups can be critically important.

It can also require some trial and error. Teams which face each other all the

time get to try out a number of different approaches until they get most

comfortable. Teams that don’t see each other often have a challenge at the

start—but fortunately both teams have that challenge. The team that figures

out how to neutralize (or at least slow down) the key threat from the other

team the fastest can get an advantage early in the game.

I don’t believe that there is any ‘best’ defender on a team. I think that this

is situational. For example, if the other team has a handler driven

offense—especially if it focuses on 1-2 key handlers—then you will likely need

a different defender than if the team plays a wide open offense that relies on

1-2 key upfield cutters to make the action happen.

Therefore, I believe, early in the game, it’s important to see if you are

simply “better” than the other team. Try to match up your strength against

their strength down the line. Best upfield defender on the best upfield cutter

for the other team. Best handler defender on the best handler defender of the

other team. If it is working, don’t change it. Win the game and get a beer.

What if it isn’t working? What levers do I pull now?

A. Defensive Call. Even in a person-defense, there are choices which I try

usually before swapping matchups. The team is killing our forehand force with

breakmarks, go to backhand. You might just make your defenders a step better

by changing the mark. Try a Zone. (“Never lose without trying a zone

defense”—just ask Fury about that.) Try changing the distance on the mark.

B. Get Fresh. Ultimate games are long. Did you ever watch Pete Sampras

play tennis? He won his service games. That was practically a given. (And you

need your offense to be similar if the game is close.) When he was receiving

serve, he often looked horrible. He’d step into the court and try to crush a

few returns. If he missed, he lost at love. If he got the first two, then he

kept at it and won. Set over. You don’t have to get every defensive point.

Rest your studs, or a few of them, on a few of the points. Get everyone as

strong as possible and make a run at the next point.

C. Switch Some Matchups. Sometimes your key defender is not at his/her

best. Switch an on field matchup. But your best on their second option and

your second on their best option. Maybe a help D shows up.

D. Think About How You Are Getting Beat. Is the other team getting deep

shots? Are they squirreling up field? Put your best defenders in a position to

stop what’s working. If they are winning with deep shots, and you have a tall

stud, use a defense that keeps him/her in center field. If your best defender

has a shut down mark, get that mark on the disc so those deep shots aren’t

quite as good or don’t get up at all.

Defensive matchups aren’t prescriptive. Like so much else in Ultimate, it’s

the team that makes the right adjustment the fastest that will win the close

ones.

Adam Goff

Offenses used to look to get the disc near the sideline and then attack from

there. Teams didn’t want to be right on the sideline—with a foot on the edge

hoping to attack from there, but a vertical stack offense looks to move the

disc to ~5-10 yards from one sideline, take a good long look up field and then

swing it around and try the other sideline. This offense can still be

effective and all teams should have the ability to use this, even as simply a

change of pace.

First, let me eliminate an obvious situation, as there is always a reason not

to do something. When the wind is strong and blowing cross field, you do have

to stay away from the downwind sideline. The wind becomes an extra defender

and it allows the defense to overplay.

All offenses have the same basic philosophy: you need to create space in a way

that gives you the advantage over the defense. This is difficult to do,

because there are 12 people upfield and it can get very crowded. On defense,

it’d be great to have 8 or 9 people on your side. On offense, often you want

to have about 4—big open spaces to throw into. Therefore, you have to make

more of the field available.

When using the sideline, you can afford at most 2 people in the area directly

upfield of the disc. The others must keep the attention of their defenders,

and keep them from poaching. This poaching is, of course, a big risk, because

the players not upfield are usually a bit less of a threat, so their defenders

can range off of them farther than usual. However, note two things about this:

First- poachers only come from one side of the field. This is different than

an attack that uses the middle of the field. Defensive help can come from both

sides of the attack. Second- if they leave the players on the far side, those

players do become threats. Immediately, the open offensive player is a threat

to take off deep (if the poacher went in) or to come in (if the poacher went

deep). So, movement and preparedness is important there.

More importantly, an attack on the sidelines dares the defense to overplay it.

The offense is all but begging the defense to come and take the sideline away.

As an offense, send the disc around and take a ton of free yards. A sideline

attack must plan to attack both sidelines.

So, a few keys to remember:

-

Having an offense that attacks the sidelines is necessary—if for no other reason than to change the look

-

Attacking a sideline requires that the offense creates space—in, out, throw towards the middle or straight up field

-

The other sideline is the key to success—all players must be ready to swing, clear space, and use it

Adam Goff

Every time a team moves the disc, this changes the defense. It puts the

defensive players out of position, if even for a short period of time. The

greater change is better for the offense, and this means putting the disc as

far from where the defense wants it to be as possible. If a team is forcing

you to throw forehand, and you get a chance to complete a pass straight up

field, you just made a good move. If you get a chance to go a little more—30°

say—then that’s a little better. But breaking the mark is just a successful

throw that happened to go that way.

I almost never think about breaking the mark. (I almost never think about the

marker at all, really.) I know where I want the disc to be, and I know where

the defense doesn’t want the disc to be. If I get a chance to put the disc

there, then I need to be ready to take advantage of that chance. To me, this

is no different than being able to take advantage of any open cut—open side,

break side, anywhere. I want all of those throws to be as easy as possible,

and to do that, I need the mark to move enough to make it easy.

I think that every move that a thrower makes has to be a legitimate move to

make a throw. Every move you make as a thrower, you are communicating to the

mark, to your cutters, to the defenders upfield. Every move must communicate

something. A “fake” doesn’t do that. Idris Nolan wrote somewhere on the

Internet that he never fakes. I believe that a fake is just a throw you didn’t

let go of: it has to look the same. Now the marker doesn’t know what you’re

doing, and moving your mark is simple. If I make a move to throw a backhand

swing against a forehand mark (if everything I’ve done so far is something I

could’ve thrown) then the marker moves just enough that I can throw little IO.

When teaching newer players (or those up-fielders who just don’t get it) about

throwing some of the more difficult throws, I almost never teach about

“breaking the mark.” I talk about the importance of it, but I teach about

moving the mark with controlled, committed motion. Every move could be a

throw. Every move is done with balance.

Another thing that I work on with players which aids in breaking the mark is

working on the shape of every throw. It’s important to put the disc in the

right shape (flat to a straight cut, a little roll into the receiver, always

leading the cut). Working on all of these shapes helps players break the mark,

even if that’s not the topic at hand.

One more thought: remember that the goal is not to “break the mark.” The goal

is to make it easy to score. It’s ok to take two throws to get it there. If

there is a gimme throw up the gut to someone who can then easily push the disc

over the break side. It’s just happened about as fast if you did it. It might

be safer, and you’re still putting the defense out of position almost as

quickly.

Adam Goff

Rich “Farmer” Hollingsworth once said that when a team is on offense, seven

people is too many (a crowd), but when a team is on defense, seven isn’t

enough. Communication is the extra player, and it’s the key to successful team

defense. For team defense, I don’t think that there is a more important skill

or a more simple one. It’s also hard to develop and I have always found it to

be really difficult to teach. It’s especially difficult for players who are

either new on a team or just on the cusp of becoming elite.

Probably every team at some point when in a huddle has talked about the

importance of talking on the field, the importance of the players not on the

field being ‘part of the game’ and about different things to say during the

game. The cliché statements often don’t work. There are only two things I have

found that work, and even then I can’t promise success.

The first is be specific in what you expect to be said. Telling people to talk

without telling them what to say doesn’t work. As an example, think about the

offensive calls that your team has. If there’s a turnover, as the handler is

picking it up, teams will often make a play called that defines what most of

the players on the field do. “Yellow thirty-seven five puppy” On defense,

you’ll only hear part of it. “Force flick.” It’s a start. But, if you add more

specific things to say, then even the most reticent player will probably use

it. “Strike” probably sounds familiar, and most people know that this means to

stop the throw up the force side (usually on the line) for a second. Define

terms for your team to use that have very specific meaning. Next, define what

the person who hears the call is supposed to do. “On a strike call, the mark

goes flat for 2 counts.” Now you’re playing team defense. “Switch” is another

call that you’ve heard. It’s meaning is pretty obvious—but even these

‘obvious’ calls should be clarified. “If you are last in the stack, and a

player calls switch, you do it. Period.”

Two quick asides: (1) I don’t want this to discourage players from saying

anything. Any piece of information is useful, so you can’t only focus on

specific calls. I watched a player turn and get a D last weekend because one

of his teammates got beat and communicated that he had been beat. What did the

player yell? “Oh s***!” It worked. (2) The things that you say don’t have to

be too complicated or secret. It’s more important that your team understands

what it needs to do than it is for you to hide it from your competition.

The second thing that I’ve found works is to do it. You can’t tell people to

talk, and then stand on the sideline looking at the sub sheet between points.

You can’t tell people to talk on the field and then cover your person without

saying anything. Leadership and example goes a long way.

Adam Goff

When I was calling subs, I also usually was calling the “strategy” for the

points. (Are we playing zone? Are we setting horizontal? Is this point the

most critical point ever?). That helped me when it came to determining players

based on the roles needed. It also made me pretty tired by the end of the day.

How these decisions are made on your team will help dictate who should call

subs when the sub-caller goes down with a freak throat injury (Larynxeum

andibenitis). For example, if there are two people who call the O and two

people who call the D, can one of them handle the sub-calling as well? That

will simplify the discussions, and it will help with establishing authority

for the sub-caller. If this is not as strict (is it just a leader on the field

who does it?), then I would suggest establishing a short discussion prior to

each point to set that down. That discussion should be 5 seconds or less.

Here’s a suggested transcript:

Sub-Caller: What’s the D?

Strategy Person: Clam for five to backhand.

Sub-Caller: Ok, (seven names) you’re in.

It is within the idea of strategy that some of the subtleties that I believe

are the hardest to convey to a new sub-caller appear. A few examples:

- It’s double game point and we’re receiving. Perhaps one of my top handlers

is also one of my higher risk handlers (bigger throws, less prone to

possession) or maybe one of my top handlers has a habit of tightening up on

the big points. Do I need that person on the field or is it too high a risk at

that point in the game?

- The other team is kicking our butts by sending out three tall receivers,

but it’s the mark getting broken that is setting up the throws. Do I need my

best markers or tallest players (or both)?

Given the parameters of the question, I bring out a pad of paper and a pen for

stuff like this. The strategy leadership needs to pass this information to the

sub-caller. This needs to be communicated during the game, and the number of

people who are allowed to talk to the sub-caller about this has to be limited

for a new one. That needs to be established prior to the weekend with the

entire team.

Sub-calling starts early in the season and lasts throughout the year. This

doesn’t just mean the act of calling out names between points, but rather

consists of preparing people for the role that they will play, ensuring that

they know that role and clearly communicating expectations throughout the

year. If the fourth person down the depth chart of O handlers who has never

played a D point actually expects to go in when you’re pulling at 14-14 in the

semis of regionals, that’s a personal problem. Sub-callers and captains need

to ignore that at all points at Regionals. It’s more likely that someone who

is down the depth chart a bit starts to think that they should be playing more

at the end of games. This is still a personal problem, not a team one. It only

becomes a team problem if it distracts leadership from their roles. If I’m

training a new sub-caller, I tell them that during the game is not the time

for this, and they just need to send that person to me or to a different

captain at that point. The sub-caller can’t spend time on it. No need to yell

at this person, but the sub-caller needs to simply-and-firmly tell the person

to go away until after the game. Then, I’d suggest that the person only talk

to the captain, and the captain talks to the sub-caller (assuming they are

different people). That message also needs to go to the entire team before the

weekend. Captain to team: “Billy-Jean will be calling subs this weekend. Do

not insert yourself into this process. If you have a problem with this, talk

to me. If Billy-Jean asks you to do something, play or sub out, do it.”

Most teams have defined positions or roles (O/D, handler/upfield, more

points/less points, zone breakers, upwind players), and the general theory of

the team has likely been discussed prior to the week of Regionals

(fortunately). The sub-caller should understand these key principles and who

fits into what roles. A hierarchy can be important to understand as well. Some

teams seemed to have a group of individuals who can self-sub (Did it look like

DoG was calling subs on offense when they were winning? Or did 7 people just

kind of wander out on to the field and then score?). The sub-caller absolutely

has to know who can and cannot do that and has to have the confidence and

strength of personality to stop those who can’t do it and sometimes stop those

who can do it.

When I called subs for teams, I kept a sheet of who had played how many

points. I changed organization of the sheet depending on the team, but:

- For teams which were almost exclusively O/D, I would split the list that

way. This presented some challenge for the few players who did play both, but

it was helpful. Then, within the groups I split handlers and upfield cutters.

- For teams which were not as heavily O/D, I split handlers and upfield. This

is what I did almost always. I expected some variance, but usually wind, the

type of O or D, the situation dictated which of those groups I needed more

than anything else.

I would refer to the sheet occasionally through the game, but not necessarily

on every line call. I also had others helping keep the sheet filled out so

that I could pay attention to how the game was going. I asked those people to

tell me things like: if a key player has played four or more points in a row

early in a game, if a player we’d need at the end of the game hadn’t played in

six or more points, and so on. Just those things are enough to help guide what

needs to be done. When I coached, I did the same thing. In addition to the

points-sheet, it’s useful for a new sub-caller to have a sheet which has the

roles and hierarchy. For example, that sheet might have four sections:

Vertical O, Horizontal O, Person D, Zone D. That’s the playbook. Laminate it

and tape it to the sub-callers arm. Within each section, it would list in

order of hierarchy, handlers then upfielders. That’s the sheet that person

would use most often. I didn’t actually carry this, as I felt that I knew it

by the time it mattered, but if someone is doing it for the first time at

Regionals, it will help.

I didn’t keep turnovers, O/D or other information on the points sheet, because

that was simply more information than I could process while making decisions.

If others put the information on the sheet, I thanked them nicely and then

ignored it. It’s good information to have when evaluating how things went, but

just too much for the heat-of-the-moment. Some people may be able to process

all of that information, but I kinda doubt it. My feeling was that, unless a

key player was having the type of hellish game that was obvious to everyone,

that person didn’t sit more when it mattered. Play time is usually earned over

a season, not in the 1 vs. 16 game at Regionals. Likewise, if a player down

the depth chart had earned more points, it’s obvious.

One special situation: Let’s say my team is pretty much O and D split. Let’s

say the O isn’t getting it done. We had a three point lead. The handlers seem

spent and we’ve turned it over two in a row, and it’s now tight. My D line has

2 of my best handlers on it. Do I put the two D guys in with the rest of the O

line? Do I put seven from in the D line to play O? To oversimplify the answer:

If I practice almost entirely split between the lines or if my D plays O

differently than my O, I put in the D line. Otherwise, I put in the D handlers

with the O line.

Special Mixed Note: I’ve seen a number of teams that have a woman sub-caller

and a male sub-caller. Those two tend to work together on some teams and

independently on other teams. I think it’s natural that the players are aware

a bit more of their gender on the field. It’s important that the “new” sub-

caller get with the other sub-caller in this situation and understand when to

and when not to worry about what the other one is doing. Both are still

subservient to the strategy role, but they need to know how the roles work

together.

And a final point about picking a sub-caller: some people with all the skills

(confidence, authority, perception, know the players, see the game) can’t

manage to call subs and play at their top level. Some can, but some just

can’t. If someone struggles to focus on their own game when they are calling

subs, that person can really only be the sub-caller if they don’t have to play

at all. Perhaps the editors can twist an ankle on that person and make this

assignment easy? (Editor’s Note: No.)

Adam Goff

Just like throwing, catching comes from practice.

How often do you see someone throwing before a game focus really hard on the

throw and not on the catch? You’ll hear this player swear and scream when they

miss a throw, and then catch the throw that came back with one hand while

joking with the person next to them.

On Z, we used to do the a throwing medley at the start of every practice and

every game. This throwing drill consisted of 50 throws and 50 catches for each

person. It involved circling so that you saw every wind. That was more throws

and catches than most players had during the rest of the day. Everyone on the

team knew this because the captains reminded us. So, everyone did it and

focused on it. During that medley I made sure that I leaned in to catches,

leaned and stretched in, used two hands when it was right. If you were lazy,

someone yelled at you. So, you caught the disc. This works for some and not

others, but it worked with that team for years.

As someone who primarily played near the disc as a handler, I definitely felt

that I was a little lucky in the area of catching. The difficulty of catching

dumps and swings is definitely lower than that of catching come-backs. The two

most critical components of the catch were focus and positioning rather than

skills with the hands. Body positioning, for me, primarily consisted of making

sure that I got my body between the disc and my defender. This enabled me to

make the catch that I wanted to make. I’d work on catching while leaning in,

either with the claw catch or the pancake. I practice that in the medley and I

used it in the games. Dump and swing throws were usually targeted for around

the shoulder height, because they are tougher to D. Again, something to focus

on.

For me, I thought of catching as fairly regimented. If the catch was between

the knees and eyes, then it was a pancake. If it was over the eyes, it was two

hands (claw), usually with one hand stopping it while the other grabbed it. If

it was lower or a layout, than I worked to get 4 fingers instead of a thumb

under the rim. That’s how it was going to be caught, so that’s how I practiced

it.

The other thing that I thought was important, and especially important for a

handler was the ability to turn a catch into a throw extremely quickly. Again,

practice it.

Adam Goff

Choosing a favorite zone depends on a few factors, including the personnel on

my team, the personnel on the other team, the direction and strength of the

wind, and the things the other team are doing that are working. Every team

should have two different zone looks in their arsenal, ideally with a well

practiced ability to transition out of the zone into a person defense.

Choosing a zone is another question though, so I’ll go with the classic—the

2-3-2. To make sure we’re all thinking the same, the 2-3-2 is the name for

what is usually thought of as the ‘standard zone’—a three person cup made up

of 2 points or markers and a top-of-the-cup or middle-middle, two wings and

two deeps, usually deployed as a deep and a short-deep. I like this zone for a

few reasons:

1. The zone can be played very simply.

It is easy to reduce the positions in the zone to very specific

responsibilities. The cup can’t let the disc through and up the middle; the

wings have to prevent the disc from going up the sidelines after a swing; the

deep has to protect from the long throws. The short-deep is a bit less

specific, but has a very defined area of responsibility. Of course, there are

more complexities than this when choosing when to take chances, how to trap or

how to transition, but it is still easy to define responsibilities.

2. It is easy to communicate.

Because positions are well defined, it is easy for people both on and off the

field to help the players in this zone with good directions. A well practiced

team is able to do this with whatever zone that they are using, but the 2-3-2

has some very obvious, basic responsibilities that make this easy to do. With

any zone (any D, really), communication is the key to success and this zone

makes that easy.

The 2-3-2 is really designed to force the other team to complete a lot of

passes and get opportunistic blocks. At the top levels, teams aren’t going to

give the disc back a lot just because they have to throw a lot of passes. A

very strong wind will help, but it still takes a bit more work. Many of the

turns that I’m hoping to see will be due to impatience—trying something a bit

tougher that gets blocked after a lot of throws that didn’t get a lot. The

other D’s will be due to a change—someone on the defense doing something

opportunistic that is a little different. For example, when everyone on the D

does exactly what they are supposed to for 5-8 swings in a row, the offense

may get a touch complacent. The wing then cheats in and swipes that next swing

when the handler didn’t quite look him or her off. This can be done all over

the field, but it relies on the rest of the team being ready to cover up when

the player takes a chance.

Two weaknesses of the 2-3-2: First, if the disc gets downfield of the cup

(either over the top or through the middle), the offense often has more

players available than there are defenders. With three defenders in the cup

behind the disc and likely one or both of the wings off toward the sidelines,

it is common that the two deeps are contending with three offensive players.

Adjustments for this can include the short-deep being very aggressive, almost

joining the cup to make going through even that much harder or ensuring that

the wings push towards the middle whenever possible. This forces the wings to

recover very quickly if the disc swings. This is because the second key

weakness is that on a swung disc, there aren’t a lot of defenders over there

until the cup catches up. Fortunately, there usually are enough defenders, as

long as the wing and short deep shift with the swing. This article isn’t

really about how to play all of the positions, but as the throw up the

sideline is the most dangerous throw against this zone, it is critical that

the wing move to the sideline as the throw goes up. If the wing is in

position, and the short-deep has moved over as well, the cup doesn’t have to

sprint with every throw. This enables the cup stay together as a unit longer

and keeps them from tiring.

Often, if a team is beating the zone, I encourage the team to get back to the

basics of the zone—focus on the responsibilities listed above, as it is often

a breakdown in the simple responsibilities that is creating the problem.

Outside of that, I consider using a transition (zone-for-five), switching

zones or alternating D’s.

If you had only enough time in one time-out to talk to a single player in your

zone D, which position would that be? What might you tell them to adjust? It’s

hypothetical—so here are two answers: If the disc is going up the sideline for

yards, I talk to the wing. This typically means that the wing isn’t recovering

to cover an offensive player on the sideline fast enough on a swing. I usually

tell the wing to ’look for that person with your whole body’ when the swing

goes up. This means that, when the throw goes, the wing turns and runs while

looking. If there is no one over there, there will be plenty of time to get

back to where s/he was. If they are going through the middle (or over the top)

of the cup, I talk to the short deep. Usually it involves telling this person

to get more vocal (it’s hypothetical, so I’m guessing here). If the short deep

gets too quiet, not helping the cup adjust, then the disc can get through the

middle more easily.

As a final aside: I’ve tried to answer this question without getting into too

many details about the difference between Women’s, Open, and Mixed. I touched

on Mixed specifics in Feature No. 1. I wouldn’t change a lot of the basics of

the 2-3-2 from Open to Women’s. I might lean a bit more towards a 1-3-3 or a

transition in Open though.

Figure No. 1

Figure No. 1